We think that, by and large, our species rules. Occasionally nature reminds us who really is in charge with floods and draughts, heatwaves and wildfires, earthquakes and tsunamis, hurricanes and volcanic eruptions, sinkholes, zoonotic diseases and on and on … and still we think, by and large, that we rule, that we are the pinnacle of creation. And with the big brains we were given, we often think we know best.

We could learn, of course. From repeating (or rhyming) history, from past mistakes, we could learn, but if you look back over the course of the past few thousand years, while we invent a great deal and change a great deal, we don’t really seem to be learning a great deal. It is quite obvious that humanity has risen to the top because we are - we can be - excellent collaborators.

Pardon the long preamble. But the wolf’s story is our story. The tales of our species are entwined and there was a time when we did, and very successfully so, collaborate. Unfortunately, the human species, instead of learning, often forgets and then, through chaos, starts from scratch.

And so we learned from the wolf, we collaborated with the wolf, then switched gears to persecute the wolf, then we protected the wolf and now … see-saw, up and down, back and forth. Now, more than ever before, in light of the biodiversity loss and climate change crises, a collaboration (not just coexistence) with the wolf could help get us out of the mess we have created.

So how did we get here?

A leap of friendship

In prehistoric times, we lived in a state of fruitful and deadly symbiosis with the wolf. Wolves were on equal footing with our species. There were vast territories and there was prey for all. There was a healthy respect between these two predatory species. Each knew that the other was capable of killing and so they gave each other room.

Our species probably greatly benefited by learning from wolves (we were still good at learning then!). Might we have learned to successfully hunt in groups from observing wolves?

“The first wolves to take up with humans were exceptional animals capable of making “a leap of friendship” with a creature from another species. Once that leap was made, Homo sapiens and Canis lupus evolved together. The hunter-gatherers learned a few tricks from wolves that also benefitted. Early human hunters were ambushers, while wolves were pursuit hunters. Humans observed wolves and learned to hunt by stampeding prey instead of ambushing. This method produced more meat than humans could eat or carry away. They left the remains for wolves and scavengers. With each bite of meat, wolves were reminded of how they could benefit from human hunters.” (Mark Derr, from his book “How the Dog Became the Dog”)

It is commonly held that humans and wolves began associating, one might say collaborating, around 15’000 years ago. One more controversial theory goes far further back: Professor Pat Shipman thinks that our species and the wolf came to work together 40’000 years ago - and that it was our collaboration with the wolf that allowed our species to end the reign of the Neanderthal in Europe.

Whether 40’000 or 15’000 years ago, the seed of domestication was planted - and this was long, long before agriculture, long before other wild animals were domesticated. The wolf is the only large carnivore that formed a symbiotic relationship with humans. Makes me wonder, of course, how things might be different, if humans had also formed similar relationships with, for example, bears!

With indigenous peoples and ancient cultures, the wolf often featured prominently. The wolf was respected, esteemed, admired, seen as a protector against evil, sometimes worshipped as a deity. But then along came agriculture (8’000 to 10’000 years back) and things started going downhill from there. And eventually there also came a new religion that proclaimed that God had given man dominion over all living creatures on Earth (Genesis 1:26-31) … and things went from bad to worse.

Once there were settlements and livestock and a clear line had been drawn between the wild wolf and the domesticated wolf-dog, the wolf became the enemy.

The rise of the wolf hunters

Charlemagne, in the early 800s, ordered the establishment of a unit of wolf hunters, called the Luparii - this became the French Louveterie, a group of professional wolf hunters that (on and off) is still around today. Charlemagne, as the father of Europe, laid down many rules - and in one book the rules were spelled out for the stewards of his many rural estates and how they should manage them. In article sixty-nine it said:

“They shall at all times keep us informed about presence and number of wolves, identification of territory covered by hunters, and numbers of wolves killed - all skins shall be delivered to us. In the month of May they are to seek out the wolf cubs and eradicate them with poison, hooks, wolf pits and hunting dogs.”

It was abolished almost one thousand years later after the French Revolution - but formed once more a few decades later. From 1818 - 1829, the French killed 1’400 wolves every year. Wolf numbers decreased and decreased until, by the end of the WWI, there were no more than 200 wolves left. This is just one of many European examples, of course. As our populations grew with more farms and towns and livestock, the stories about the wolf were reversed. Now the wolf was evil, the slayer of children (Little Red Riding Hood being the famous cautionary tale, of course), the killer of the innocent lamb, the curse of the werewolf, etc. etc.

First in England, then in Scotland and then in Ireland, the wolf was hunted to extinction. On mainland Europe, luckily, the wolf could travel, could escape, could find new territories aways from pikes and guns - if not for the fact that nature doesn’t stop at national borders, there would be no more wolf today. As is, they could run, find new ranges, across the Alps and further East.

They were relentlessly hunted across all of Scandinavia and by the 1970s they were eradicated, except for the few that used the open borders with Russia. Germany, Switzerland, Slovakia, Balkan states, Romania, Greece, Spain … every country you look at, the wolf was either entirely killed off, or at least massively decimated. The whole story of wolf hunting across the globe over the course of the last two thousand years is laid out here.

And then … a pause

In a way, technology brought about a reprieve for wolves. As the industrial revolution grew, bringing ever more people from the countryside into the cities and their factories, farms were abandoned, homesteads were left behind, with younger generations no longer interested in tending land and keeping livestock. The 1950s saw far fewer people working in rural economies - and that meant more space for nature. Little by little, wolves realized that there was, once more, room to roam. And where fewer people were, the potential for conflict was lessening.

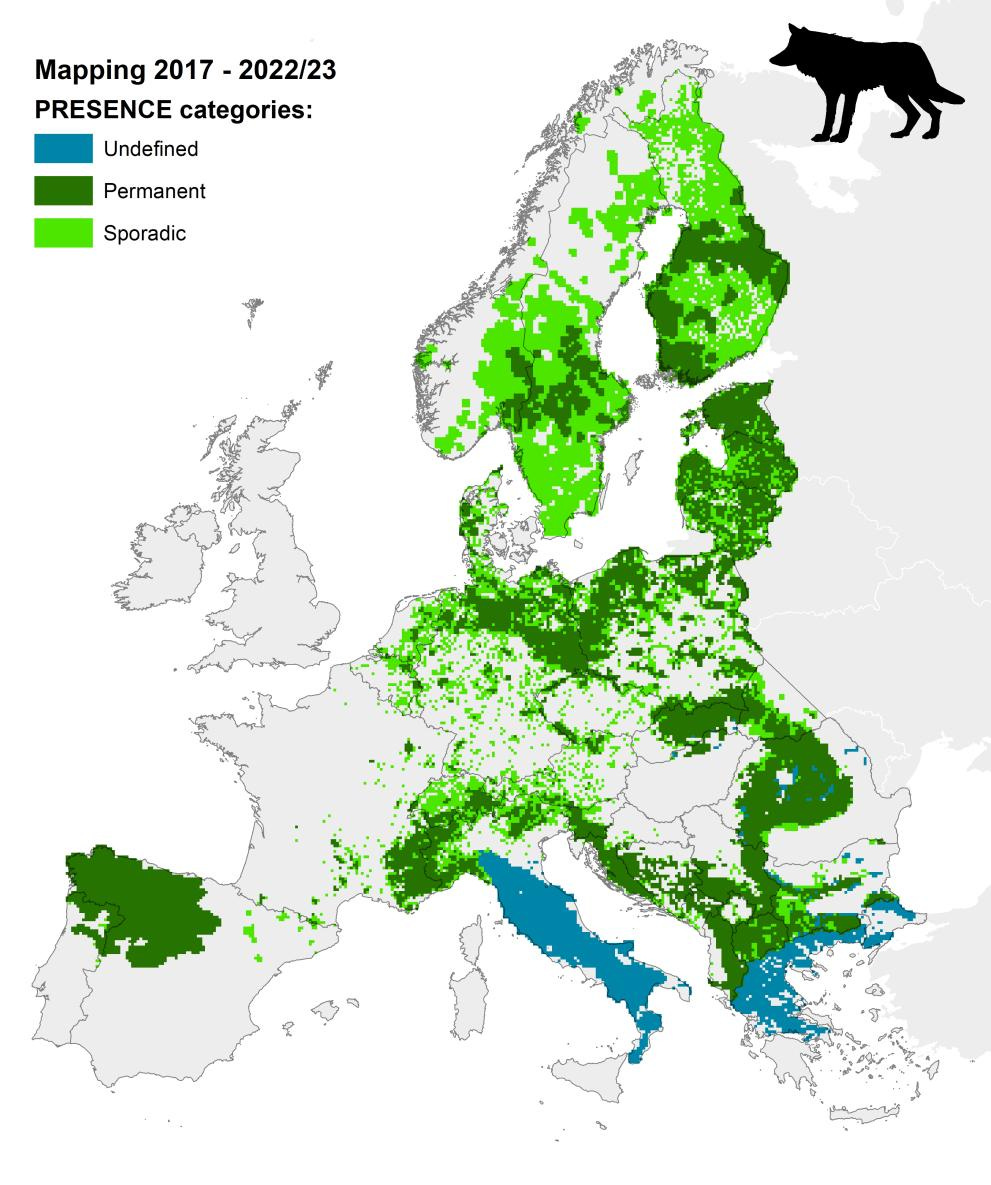

In many regions, the wolf had been completely eradicated … now they began to slip back in. After having completely disappeared from central Sweden, they popped up again in 1978 - and little by little, with minute populations, made Sweden and Norway home again. When you look at the below map, you may feel heartened by the return of the wolf in various parts of Europe. But remember that many of those wolf population are slim, at best. In the 2000s the first wolves were sighted again in the Netherlands, Belgium, Denmark and wolf packs are also back in Germany.

It turns out that Poland is a particularly good wolf ally. According to the Polish organization Association for Nature Wolf , the country is home to as many as 2’000 wolves. That’s good news for the wolf, but the real importance of Poland lies with its location. As a central European country, it represents an excellent hub for wolves to travel across borders, helping wolf packs in other regions gain strength in genetic diversity. The Association for Nature Wolf writes:

“The Polish wolf population makes up the western-most range of a large, continuous Eastern European wolf population, which has retained a high level of genetic diversity. In other areas of occurrence of this species in Europe, e.g. Italy, France, Spain or Sweden, populations are more isolated, limited in number and genetic diversity, and very sensitive to environmental changes. Poland, due to its location in the central part of Europe, is one of the most important refuges of this carnivore, and is an important source of dispersing individuals to regions where it was eradicated many years ago. Analyses of changes in wolf range in the twentieth century, genetic studies on wolves in Poland, radiotelemetry and GIS analyses show that wolf migration and dispersal in Poland occurs along latitudinal migration corridors. These findings resulted in a project of protection of migration corridors for big terrestrial mammals in Poland.”

The rise of environmentalism

Let’s face it, the subjects of climate change and degraded biodiversity only seeped into mainstream consciousness over the course of the past ten years. But, luckily, it doesn’t take mainstream to act. Scientists began publishing about the dangers of the changing climate some fifty years ago. Then policy experts and ecologists got together out of concern for natural habitats and endangered species. This brought about the Bern Convention on the Conservation of European Wildlife and Natural Habitats (1979) and the EU’s Habitat’s Directive (1992).

The paucity of biodiversity across much of Europe became more known - and eventually the connection between climate change and biodiversity loss was recognized. The past decades have also given rise to an increasing understanding of the wolf as not just an apex predator, but as a crucial element of the trophic cascade and a prime ecosystem engineer. The story of Yellowstone’s wolves, which began in 1995, has been told in many ways, shapes and forms by now - it’s still a good one. You’ll have likely seen below clip (heck, it’s been viewed forty-five million times!).

But here’s the thing, the Yellowstone is vast and remote, whereas much of Europe is built-up, heavily populated and heavily fragmented. The Yellowstone story was one of “simply” reintroducing the wolves, affording them protection, and then watching the rise of biodiversity, the many positive changes with both fauna and flora, unfold over the coming decades. And even there they had to deal with challenges, with traditionalists, with detractors from every corner.

In most of Europe, people - and in particular farming and hunting lobby people - went haywire with artificial outrage whenever even a single wolf showed up anywhere and did what a wolf is supposed to do, and that is to hunt and kill its prey. Over the course of the past ten years, those lobbies’ marketing machines have gone into overdrive, have spread falsehoods, have fearmongered with the best of them, have assailed and misinformed and threatened politicians - and so the best that could be achieved was to keep a bare minimum of wolves alive.

According to the IUCN there are clear guidelines that define when a wolf population is no longer threatened with extinction. For a population of wolves to not just barely hang on, but thrive instead, they need to be safe from human slaughter, and they need to be able to roam. Genetic diversity, remember the above mentioned Poland? The IUCN states that, if a wolf population can roam to maintain genetic diversity, then around 250 mature wolves are considered sufficient. But if the population is isolated, there need to be at least 1000 wolves.

Numbers and fragmentation

In the latest Large Carnivore Populations report by the European Commission, booming numbers of carnivores (bear, wolf, lynx, wolverine, golden jackal) are reported. At the same time, we hear of countries downgrading protections and slaughtering carnivores in the hundreds. Let’s stick with the wolf - according to the report, there are currently around 23’000 wolves (up 35% from 2016) across all of Europe. That certainly feels positive, doesn’t it? But don’t be fooled.

Look at the above map and you’ll see that many European countries are practically devoid of these essential ecosystem engineers. Just because numbers of wolves are on the rise, doesn’t mean that biodiversity is in a good place in Europe. Degraded, mono-cultured, over-industrialized landscapes will change and improve (and as marvelously as in Yellowstone), when we allow wolves at our doorstep. As uncomfortable as that sounds, that is when nature will begin to dramatically improve.

According to the 2023 report that comes up with the 23’000 wolves in Europe - the numbers break down as follows:

The Dinaric-Balkan population is listed as approximately 4’700 wolves. These are in and roam across Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia & Herzegovina, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Albania, Serbia, Kosovo, Greece and Bulgaria.

The Carpathian population is about 4’000 wolves, roaming Slovakia, the Czech Republic, Poland, Romania, Hungary and Serbia.

The Baltic population is about 3’000 wolves. This population roams in and across Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania and Poland.

The Central European population also consists of around 3’000 wolves - sounds good, right? This number includes wolves roaming in and across Germany, Poland, Netherlands, Denmark, Belgium, Luxembourg, Austria and the Czech Republic.

The Italy Peninsula population is listed as an exact 2557 wolves.

The Iberian population (Spain and Portugal) is around 2’400.

The Alpine population is about 2’000 wolves. They live in and roam across Italy, France, Switzerland, Austria, Slovenia and Germany.

The Scandinavian population of Norway and Sweden is 520 wolves.

The Karelian population of Finland consists of 310 wolves.

Have you taken a closer look at the above list? Have you noticed that some countries (especially Poland) are mentioned several times? Yes, wolves need to roam - but I cannot help but wonder whether or not this country or that has embellished their numbers with wolves that are mostly at home in Poland.

Take the example of Austria: While it is listed as part of the Central European and Alpine wolf populations, it had a reported mere 58 wolves in 2022. Or take the Netherlands with 63 wolves, or Belgium with 28 … and huge territories such as Finland and Norway and Sweden have, compared to their size, minimal populations.

Back to medieval times

As you see, the larger wolf populations live in remote regions of Europe. But even so, farming and hunting lobbies in more and more European countries scream out for the mass slaughter of wolves and, ideally, their complete eradication. What they do has nothing to do with good sense, and everything with tradition and politics. The wolf is not the problem. We, we are the problem. We know it, but rather than changing our ways, it is ever so much easier to point the finger elsewhere. The wolf makes for an excellent scapegoat.

Back in the days of Charlemagne there was good reason for wolf hunting. Agriculture was everything and everywhere, protections were few - and the gun had not even been invented. And a thousand years later, at the close of the eighteenth century, there were still as many as 15’000 wolves in France alone. While, back then, most people were still employed in agriculture, the picture today looks very different. Today people working in agriculture in Europe account for around 4%. That’s not nothing, that’s still millions of people - but it needs to be put into perspective.

Hunting the wolf today is scapegoating, pure and simple. We have the science, we have the experience, we know about biodiversity loss, about trophic cascades, about ecosystem engineers. We have learned about the many coexistence measures that are successfully in place and in use. We have technology on our side. We have incentives and compensation measures … and still those lobbies prefer the route that requires no change of them, the route that blames everything on the scapegoat.

In Switzerland, and exclusively in the more remote regions of Graubünden, Valais and Jura, there roam 30-40 wolf packs (they roam cross borders, too, to France and Italy). Even though the science is clear, the knowledge is there, as are coexistence measures and compensation, Switzerland caved to lobbies and allowed the slaughter of 80 wolves in 2023. In 2024 they went even further, killing 101 wolves - a whopping third of the entire population. Officially the wolf remains a protected species, but lobbies are actively engaged - and successful - in undermining protections, slaughtering entire packs. What happens in Switzerland, happens in other European countries, too - here, for example, is the same story playing out in Sweden.

The latest lobbying success is no doubt the lowering of wolf protection by the Bern Convention this past December.

The way forward for nature hero wolf

I’m none too hopeful, I’m afraid. While hundreds of organizations and scientists rally and howl for the rights and importance of the wolf, political bodies seem to willingly cower left and right before the supposed might of various lobbies. As the past has shown, the pendulum swings this way and then that way and even though our vast brains are capable of so much, we appear unwilling and/or unable to learn from everything we do know.

The better choice is clear. The better choice would be to stop that insidious pendulum from swinging in the first place. There should no longer be a “for nature” and an “against nature”. The human species has exploited nature with ever-increasing ability. Human over nature, human apart from nature, human better than nature.

Remember when you were a kid, playing in the mud and eating dirt and those were the most normal things in the world? When you roamed the thickets and came back with scratches and bruises and an occasional tick? When playing in nature meant being one with nature? New generations are often growing up apart from nature. And even if they feel an uncertain yearning for being out there in nature, they have been taught to fear it. Aside from legislating nature-positive changes, this can and must be tackled by all of us in two ways:

Getting out. Children, from an earliest age, must be given the chance to experience nature. Bees and ants and slugs, the wonder of seeing a fox play with a litter of cubs, the magic of a hedgehog, the majesty of a stag. The smell of the proverbial rose is a great thing, but so is grass! Chew on a leaf, eat a petal, lick a pebble. Get out there and experience being in nature. Billions of people on our planet have lost touch with nature, cannot feel it, do know know it - and what you don’t know, you cannot love, respect, care for. The Nature Pyramid should be the guiding light for any family, any school - anyone, really.

Rewilding! As the movement continues to grow, more and more nature will recover not just in remote places, but where most people live. Florence Williams, author of The Nature Fix, put it plainly: “Given that more than 70 percent of the U.S population resides in urban areas, bringing nature into cities should be a top priority.”

However, in the past that has always meant that we create parks like New York’s iconic Central Park - parks that are manicured, safe, domesticated. My take would be a bit more uncomfortable - and that brings me back to the wolf at our doorstep. Yes, we need more nature where people live - but that needs to be real nature, one where the human touch is light, if at all. One where animals have as much right, and as much protection, as we expect for ourselves.

We need the planet, its flora and fauna, its land- and seascapes, to thrive. We need biodiversity-rich nature, we need vibrant, healthy, sustainable ecosystem … we need the wolf.

Cheers,

If you enjoy the Rewilder Weekly …

… please consider supporting my work. Your paid subscription will help generate the funds needed to realize a unique rewilding book I’m working on. And, of course, that paid subscription also ensures that the Rewilder Weekly will always keep going for those who cannot afford to pay. A thousand thanks!

Excellent post! I’ll share it widely, as this needs to be understood much more broadly.