The GPS-tracking of animals greatly assists in monitoring recovery efforts of an increasing number of species. It helps us understand how they move, how they behave, how they migrate, where challenges arise - even how they evolve over generations … but did you know that they may also be able to help our species prepare for earthquakes?

A few years ago I was invited to join a conference focused on the latest advances of artificial intelligence. I had been to several such gatherings and the presentations usually stayed about the same and didn’t exactly fascinate. But then there was this one presenter, an ornithologist with a lecture entitled “Tracking Wildlife: When Animals Predict Catastrophes” … it was a catchy title - you bet I attended!

The man was Martin Wikelski, and aside from being a bird man he was also Managing Director at the Planck Institute's Institute for Animal Behavior. It was instantly clear that the professor’s interests went far beyond birds. He also was (and still is) the Director of ICARUS, an international cooperation for the observation of animals from space. What he showed us was fascinating in many ways.

“We’re spending a great deal of time talking about artificial intelligence ... let’s start making use of natural intelligence.” (Martin Wikelski)

We have to track animal species for their own sake - nature protection and nature recovery efforts need monitoring to be successful. But, as I’ve learned during that presentation, our species can also make use of the natural intelligence of other species - for example as early warning systems.

Animal senses are far more intact than ours that have been dulled by civilization. Our eyes, our ears, our hairs, our instincts, all blunted compared to what was, aeons ago. But animals are still far more in tune with nature (even if that civilization of ours makes it harder and harder on them). They sense changes in the air and in the earth. They also act based on what other animals do - they respond the changes in the animal networks.

“Animal senses, which are often superior to human senses, allow them to respond to environmental changes as well as to natural catastrophes such as earthquakes or volcano eruptions before humans even notice them. The animals will thus be our sensors with which we will feel the pulse of the Earth. Hopefully, with the aid of these animal sensors, natural catastrophes can be predicted, the spread of infectious diseases tracked, climate changes identified and threatened species be better protected. And last but not least, the scientists will learn a lot about the life and behaviour of animals.” (ICARUS)

The goats of Mount Etna

ICARUS put transmitters on goats and tracked those herds as they grazed around Mount Etna, a still active volcano in Italy. Researchers recorded unusual movement by the goats hours before volcanic eruptions.

These days sensors of all shapes and sizes are used for just about every species. The aforementioned goats? Easy. Anything with a neck is easy, right? But with technology becoming ever better and ever smaller, sensors on birds, on fish, even on insects are in use. With trackers that are solar-powered and practically weightless, they can remain operational for the duration of an animal’s life.

For now there’s still not enough data for scientists to take this “natural disaster prediction” to a next level - but yes, they can already clearly see that animals can be predictors of a volcanic eruptions, of earthquakes, of tsunamis.

And then there’s climate change

Researchers track species migrations. But in our times of changing climate, the focus is very much on migratory changes. Do migrations happen earlier? Or later? Do they change routes? If so, what are the reasons? Temperature changes? Droughts? Lack of food? Other threats? Animals may be - just as the canary in the coal mine of yore - early predictors of climate change dangers ahead.

From MIT’s Technology Review: “Outfitting even small animals with lightweight, inexpensive GPS sensors, like the one on this blackbird, and monitoring how they move around the world could provide insights into the global effects of climate change.”

We always think of ourselves as the savior species (even if we know that we’re most definitely also the destroyer species - but as a savior species we try to make up for some of the havoc we keep wreaking). But there’s definitely a better way of looking at it - and that is not that we are benevolent and caring and only want the best for those species, but that we need them a great deal more than they need us. If more of humanity would realize that we’re not “just” protecting/saving/restoring species for their own sake, but also for our own survival, more people might see the light.

The next virus is coming

Because of global air travel, humanity hops from one place to another within hours, sometimes bringing along pathogens. But, as we’ve all learned the hard way, animals are also well documented to be the bearers of viral news. Birds in particular, as they migrate over vast distances, can transport diseases across the globe.

Between 2005 and 2010, researchers analyzed the outbreaks of the H5N1 virus among wild and domestic birds, a virus that is also dangerous to humans. GPS transmitters helped them follow the flight paths of the bar-headed goose and the common shelduck.

Thanks to that research it is thought that the common shelduck is infected by poultry in its wintering areas in Bangladesh. The bar-headed goose, on the other hand, comes into contact with the H5N1 pathogen mainly in the Tibetan capital of Lhasa and brings it from there to China. Such research makes it possible to pinpoint dangerous zones and to then isolate domestic animals from wild ones.

7.5 billion locations

ICARUS isn’t alone in tracking animals, of course. Many organizations are involved, and the recorded data comes together at Movebank, an online database hosted by the Max Planck Institute of Animal Behavior. The more data, the more telling the results become, as you can imagine. The many billions of data points collected there on a real-time basis help thousands of researchers and wildlife managers around the world.

In a 2024 newsletter, Movebank highlighted that the database comprised, at that time, the movements and behavior of over 200’000 animals and 1’383 species - with over 11 million new data records added every day. To get a sense of just how much, and how globally, this tracking happens, watch below clip.

The biodiversity crisis

As you’ve seen, the tracking of animals, that natural intelligence - a veritable internet of nature - offers great promise to help with a number of big challenges. But I’d like to get back to the researchers’s focus on nature recovery and tackling the biodiversity crisis. GPS data from animals can help humans understand problems long before we’d figure them out on our own.

There’s been a massive loss of songbirds reported in Europe over the course of the past quarter century - ICARUS puts the number at a massive 30%. Rewilders are doing a great deal to help protect and nurture individual endangered species - but what does the big picture tell us? If 30% of songbirds have been lost in the last twenty-five years - where exactly are the challenges and what exactly are the drivers? With a large-scale tracking effort of common songbirds, researchers could learn a great deal.

The latest ICARUS project aims to track common songbirds, from where they live to where they migrate, to learn about changing behaviors and to hopefully discover the factors that have caused their massive decreases over past decades. For this effort to work, of course, thousands of participating researchers and ornithologists are needed to help tag and monitor birds.

Get involved

The plan is to track continuously track 5’000 individual birds from five species (kestrel, swift, song thrush, blackbird and starling). If you research birds, then you should heed ICARUS’ call to action - they write:

“We seek collaboration with experienced bird ringers and ongoing research projects across Europe. Our partners will capture and tag birds during migration or nesting periods, providing crucial data on their movements and mortality. Do you work with these five species? Are you involved in bird research and interested in enhancing your work with tracking data? Do you regularly capture these birds and want to track their fate—when and where they may die? If so, we invite you to join us! 👉 Go here for application details

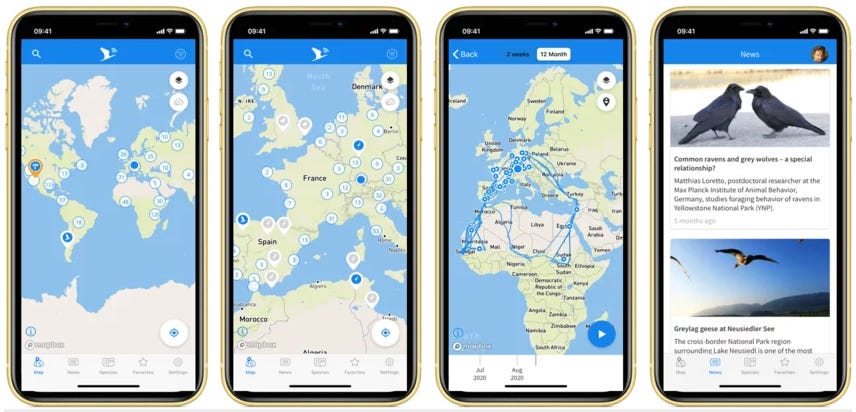

And if you’re no expert, but simply someone who’s fascinated by the natural world and the tracking of animals and interesting in helping - well then ICARUS has something for you, too - the Animal Tracker app - and it is very much something where you and I - as citizen scientists - can be of great assistance.

While scientists collect the above-mentioned wealth of data from hundreds of thousand of GPS trackers on over one thousand different animal species, those scientists are rarely there, in the field, where the animal resides in that one exact moment. Scientists see WHERE the animal is at any given moment, but they don’t know WHAT the animal is doing there. This is where we can come in.

We can use the app for our own neck of the woods and if a data point pops up where we are, identify it and see what that animal is up to. Any information we can add to the Animal Tracker app helps scientists make better sense.

Finally

I have to admit, I don’t like seeing tech gadgets on animals. That’s my personal sentiment, the idealist in me who would simply like us to get out of nature’s way. But my inner realist knows all too well that any of those gadgets are there for a very valid reason. They help humanity better understand nature and support individual species where needed. And these efforts, delivered by the natural world, also deliver important insights for our own species. All of these efforts, I’d hope, will lead to greater appreciation and protection of the natural world.

Cheers,

If you enjoy the Rewilder Weekly …

… consider supporting my work. Your paid subscription will help generate the funds needed to realize a unique rewilding book I’m working on. And, of course, that paid subscription also ensures that the Rewilder Weekly will always keep going for those who cannot afford to pay. A thousand thanks!

PS: Turns out that the aforementioned Martin Wikelski has taken the time to put the insights of the past decades into book form. Last year he published “The Internet of Animals” Well, I’ve given you a brief look. If you’re interested in going deeper, that book will most assuredly do the trick.