I had read about Tree for Life’s idea of bringing the Tauros cattle to their Dundreggan lands in the Scottish Highlands a while back. I’ve been a fanboy of large herbivores for a long time, so when the opportunity to meet with Steve Micklewright, the CEO of Trees for Life, presented itself, I of course zeroed in on the Tauros!

Large herbivores are essentially contentedly roaming, peaceful creatures. From horses to cattle, and from bison to water buffalo - there are still a good many large herbivore species in existence (unfortunately mostly the domesticated kind). Beyond Europe, mega herbivores such as elephants, rhinos, hippos and giraffes still go about their business of enriching biodiversity and improving landscapes … as for Europe, humanity has long shrunk the number of species by hunting many to extinction.

“If we want people to see herbivores on rewilding projects recognised for their role in natural processes, we need to dial up the wild.” (Sara King in her article about Rewilding Britain’s support and backing for the Trees for Life project)

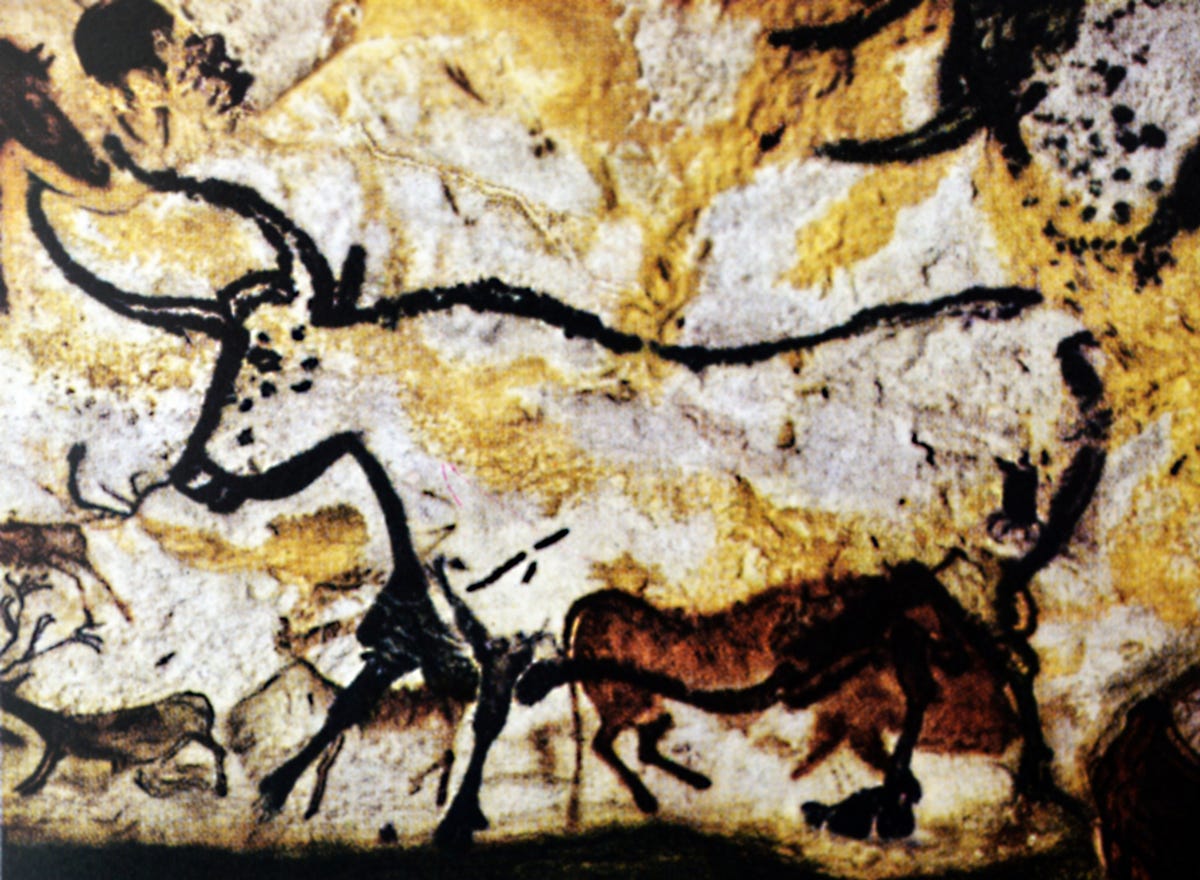

Across Europe’s prehistoric times you’d have seen herds of megafauna, most famously the woolly mammoth and the woolly rhinoceros, of course. You would have seen herds of bison and horses roaming, there would have been hippos and water buffalo, as well as that famous ancestor of domestic cattle, the magnificent aurochs.

Today there is barely anything across Europe that can be called a “vast herd” - other than livestock, of course. Alas, while domesticated cattle most certainly are large herbivores, they live on dedicated grazing lands, locked into certain places. For large herbivores to deliver on their potential for nature restoration, they need to be able to roam free.

Before we get into the Tauros, a quick word about cattle: You may have come across below visualization. The biomass of mammals on Earth is heavily weighed against wild mammals. 62% is livestock, 34% is made up by our species … and just 4% make up ALL other mammal species on Earth - and it is those few that are the “roaming free” animals as mentioned above, the very ones engaged in helping nature recover … you’d think we’d be smart enough to want to change those percentages, right?

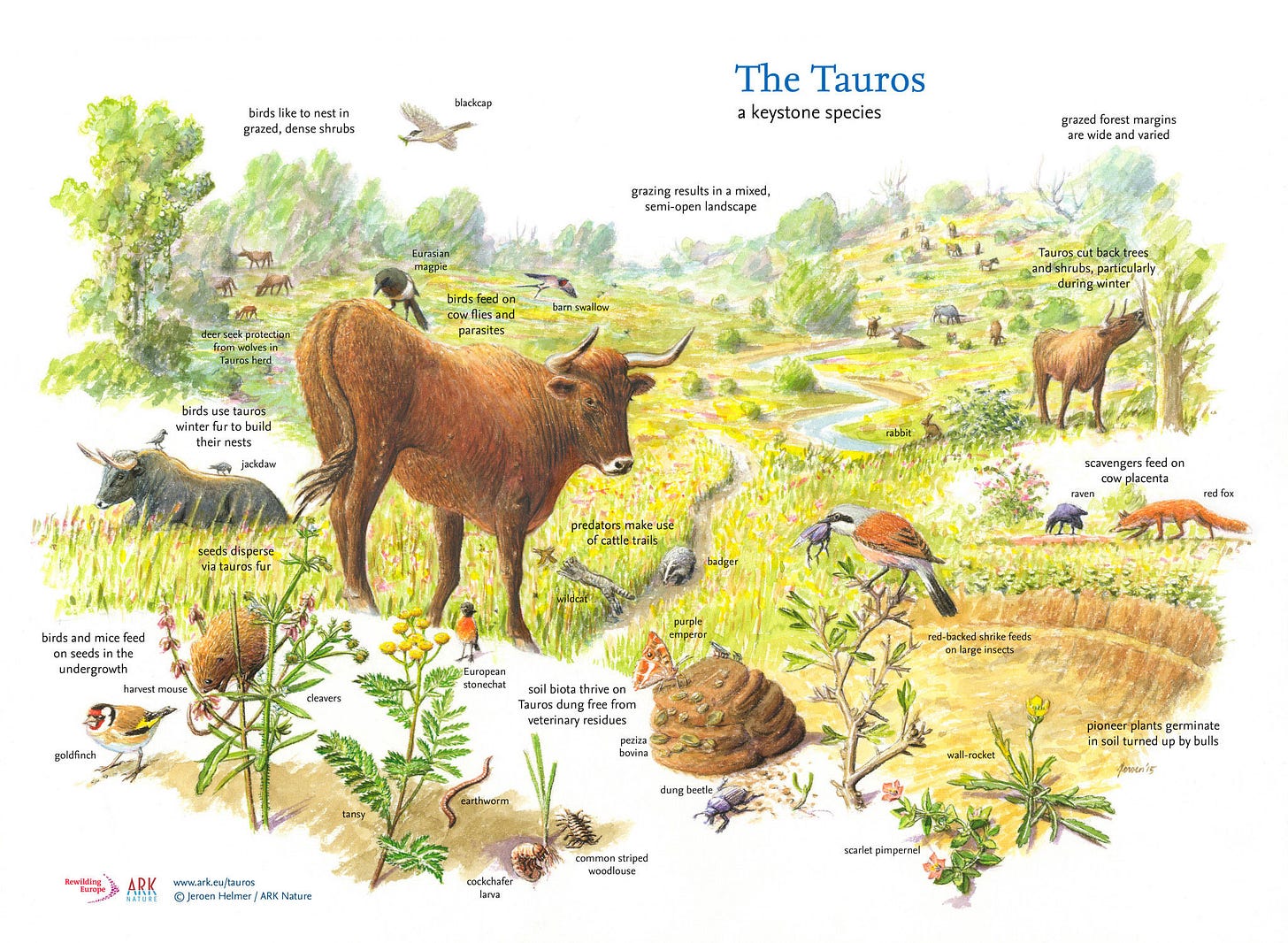

Large herbivores are simply there, simply grazing, and often majestic in stature. By going about their daily business, they act as first-rate ecosystem engineers (explore below image and you’ll get an excellent sense of everything that entails). All large herbivores are different in their preferences and behavior - and so a mix of large herbivores (just as it would have been in ancient times) is definitely desirable for healthy, biodiversity-rich landscapes.

In Europe today, much of the land is fragmented in the extreme, with railroad tracks and especially roads just about everywhere. Go here to learn more about this fragmented world - and the many-faceted harm caused to nature by 65 million kilometers’ worth of roads across the globe. There are, quite literally, countless roadblocks in the way of rewilding efforts across Europe.

But the need is urgent and obstacles often give people just the drive required to overcome them - and so rewilding projects with large herbivores are happening in most European countries. Certainly the most heartening example, and really the only example where you can speak of a vast herd in Europe, is the European bison population in Poland. There are about 2’000 European bison roaming free in Poland - hard to imagine, right? Imagine driving along a road, then a large herbivore steps into the road and you slow down … and then you wait, because this happens:

If you think I’ve been digressing form the topic at hand, the Tauros - nope! Because, before going into Scotland’s Tauros project, I really wanted you to get a sense of where we currently are - and the ideal of the above clips, with large, free-roaming herds of bison and horses and the Tauros, across Europe!

I drove to Findhorn to meet Steve Micklewright at the Trees for Life headquarters. We made ourselves comfortable in his office that held a small desk and two large couches on opposite walls. He introduced me to Matteo, his big dog - and the two couches soon make perfect sense. As we sat there, either of us occupying one of the couches, talking about rewilding for hours, Matteo took turns “nesting” with us.

Steve’s journey has been focused on nature from the start. After studying botany, nature conservation and ecology, he immediately stepped into the field of nature protection and worked, among others, for the WWF and Birdlife Malta. You could see the pain and frustration in his face when he talked about the three years of intense advocacy to increase bird protections in Malta. When I was visited Gozo - probably the same time he was there - I saw what he had been up against. Illegal bird hunting was the norm, with the landscape downright littered with empty shotgun casings.

I’ve seen this many times in my life - passionate people who engage against all odds, who believe in something, stand for something, fight for something … but there often comes a point when the very struggle that once fueled engagement begins to gnaw at one’s very identify. Steve and I talked about a few such experiences in our lives and that, at some point, for one’s own health and sanity, a change is the only sensible option. He had not been looking toward Scotland for a next opportunity - but that’s life for you, isn’t it? Things happen in often unexpected ways, exactly when you’re not looking.

Since taking the leadership role in 2016 (the shoes he was tasked to fill by Trees for Life founder Alan Watson Featherstone were huge), Trees for Life has gone from strength to strength, has grown in staff and projects (find them all here) and has opened the world’s first Rewilding Centre in Dundreggan. From trees to entire landscapes, and from red squirrels, beavers and lynx to the Tauros project - a great deal is happening!

The Tauros is a cattle that really does hark back to prehistoric times. Our species drove the aurochs to extinction. It was gone from Britain around 1300 BC. And while it survived much longer in Continental Europe, the last known aurochs died in Poland in 1627. The DNA of the aurochs, however, lived on in other breeds. You could still see the ancestor in cattle that were taller, stronger and bigger-horned than others. In the 1920s, attempts to “back-breed” the aurochs began. Crossing several breeds created the Heck cattle and in the 1990s the back-breeding continued with the intent to create a breed that would as closely as possible resemble the ancient aurochs.

Now you might wonder: Doesn’t Scotland have its own large herbivores, such as the wonderful Highland and Galloway cattle? Why would Trees for Life want to bring another cattle species to Scotland? The reason is twofold, as Steve explained:

As mentioned before, different species have different grazing preferences and different behaviors. What a Highland or Galloway herd does, is not the same that a Tauros herd does. That should in no way take away from Highlands and Galloways. They also have the capacity to deliver amazingly for nature (particularly if they were allowed to roam freely) A major component is that the Tauros is bigger and thus clearly heavier. Their browsing behavior differs, every move they make has a stronger impact on the land, on flora and fauna.

The massive Tauros most certainly makes an immediate impression! So, when nature-loving people visit the Rewilding Centre, seeing the Tauros cattle will tell a powerful story about rewilding and its global potential. Showcasing this aspect is far more difficult with a domesticated herd. When you see a Tauros with its mass and height and imposing horns, trust me, you’ll be in awe. While enhancing biodiversity is very much the task of the Tauros, the project is thus also about education and ecotourism.

“Introducing the aurochs-like Tauros to the Highlands four centuries after their wild ancestors were driven to extinction will refill a vital but empty ecological niche – allowing us to study how these remarkable wild cattle can be a powerful ally for tackling the nature and climate emergencies.” (Steve Micklewright)

So here’s the plan: Steve explained to me that the project isn’t the reintroduction of the back-bred ancestor of a once native species, but instead a five-year research project. So far, Tauros herds have been introduced in several European countries, but none as far north as Scotland. This project then is - first and foremost - about monitoring, about evaluating just how well the Tauros might be suited for the Scottish Highlands. And if this leading effort by Scotland is successful, there’s no doubt that further Taurus herds will be released in other countries with similar climate conditions.

If all goes as planned with regard to funding, then 2026 will see the arrival - from the Netherlands - of the first five Tauros cattle at Dundreggan. When all’s well and settled, a second batch of Tauros will bring the herd to fifteen.

Trees for Life’s Tauros Project is being designed to discover whether releasing them in a way that enables them to behave as naturally as possible could enhance nature recovery efforts at Dundreggan and potentially elsewhere. The project would also strictly adhere to the legal and animal welfare requirements that come with keeping cattle … There could be other benefits from tauros, including nature-based tourism and meat production. Importantly, reintroducing an aurochs-like animal is not about trying to recreate the past, but is instead about restoring rich and diverse landscapes which support a variety of wildlife, and are resilient to environmental challenges. (Trees for Life)

I think that sums it up perfectly. I’m greatly looking forward to following the progress of this project. Currently, to my knowledge, the largest Tauros herd is in Hungary, with some 500 animals. Just try and imagine that herd roaming the Scottish Highlands - it would be majestic times two!

Cheers,

If you enjoy the Rewilder Weekly …

… consider supporting my work. Your paid subscription will help generate the funds needed to realize a unique rewilding book I’m working on. And, of course, that paid subscription also ensures that the Rewilder Weekly will always keep going for those who cannot afford to pay. A thousand thanks!

Many thanks for sharing - it’s great to see these types of rewilding projects moving forward. I look forward to following progress once the cattle are there.