The return of Scotland's forests

The situation with native forests in Scotland remains dire. Nature restoration efforts make great strides in many places, but to date still only 4% of Scotland is home to native woodlands.

The reasons for the ongoing challenges are many: from the razing of woodland in the past to overgrazing by sheep and deer, and from non-native trees to the ever-present foe that is climate change. I’ve wanted to explore this a bit more - the past, the present, the possible futures. If you’re interested, tag along.

Scotland’s early woodland history

Scotland’s empire of trees began with the receding ice of the last ice age. The warming climate made it the home of the birch. It is considered the first tree to dominate the lands. Birch and pine made their home in the east and north, while oak loved the milder and rainier south and west. Hazel was another early joiner to the woodland gang. It is thought that, before humans began deforesting, that pine and oak dominated the landscapes - today, however, the birch is once more the most common native tree in Scotland.

Scottish woodlands reached their maximum extent about six or seven thousand years ago. From then on, changing climate, animal grazing and human actions began to gnaw away at what must have been a sight to behold. By the time of the Romans, Pliny the Elder writes of a silva caledonia - the Great Wood of Caledon, the Caledonian Forest. In The Great Wood, author Jim Crumley makes the case that the size of the forest was actually exaggerated by the Romans to rationalize to their leaders why they failed to proceed further north.

I’m sure the conversation went something like this: “Sir, the scouts have come back. Well, some of them have. Well, actually, one made it. He’s fine, sort of. He says that we definitely should not go further north. What? Oh no, Sir, it’s not because of the hostiles tribes, the rougher weather and the difficult territory - it’s the trees, you see, there are just too many trees. It’s a great wood, he says - we could handle tribes and weather and territory, of course - but those trees, Sir, those trees make it mission impossible. I’m sure you understand.”

Okay, the “Great Wood” likely wasn’t quite the size where “Red squirrels could have hopped, skipped and jumped between branches from Glasgow to Aberdeen and beyond without coming down to the ground.” as suggested in this article. Trees for Life explains that, by the time of the Romans, a whopping half of Scotland’s native forests had already been lost. It was still extensive, of course. To give you a sense of its vibrant biodiversity, here’s a paragraph from a Trees for Life’s article:

“Wildlife flourished in a mosaic of trees, heath, grassland, scrub and bog. Lynx prowled the denser woodlands and packs of wolves hunted deer. Giant wild cattle (known as aurochs) grazed savannah grassland, while boar rooted through the leaf litter. Bears scooped salmon from the rivers, and elk grazed in the willow meadows created by the dams of beavers. Many different birds were abundant.”

And then … agriculture

Early farmers, settling in places, grazed their livestock. They burned woodlands and heath first and foremost to encourage the growth of heather for their stock. And so it began - burning, the grazing, the creeping destruction of those far-reaching woodlands.

Eventually the potential of agriculture took hold and more and more woodland was cut down to make room for planting and grazing. Fast forward to medieval times, with Norse and Celtic peoples felling trees to build up villages, walls and ships. Later came wars and the disastrous Highland Clearances and large-scale sheep farming and the industrial revolution and shooting estates and escalating deer numbers and then the World Wars came and more timber was needed and the forestry commission was founded and non-native sitka spruce plantations sprang up … It truly is a story of woe - and the outcome of that story is clear to see for anyone visiting Scotland who’s not blinded by the shifting baseline syndrome.

Scotland’s woodlands today

Remember I wrote that there remain just 4% of native woodland in Scotland? Well, when it comes to those special pinewoods, it’s down to 1% - and those trees haven’t been protected for the longest time. Quite the contrary. The remnants of large forests today are fragmented into 38 sites (or 84 smaller sub-units). They are isolated and exposed and at a far greater danger than if they were connected clusters.

Imagine well-functioning nature like a beautiful Persian rug - its tapestry is finely woven and every thread is a key element of flora and fauna. If you pull out a thread, that rug begins to fall apart. Threads have been pulled for a few thousand years now: the removal of flora and fauna, of trees and predators, the destruction of soil, the arrival of invasive species. As for the overgrazing by sheep and deer, that cannot be called a missing thread or two - those species have chewed into that tapestry with relish, leaving ever larger holes in that once exquisite Persian rug.

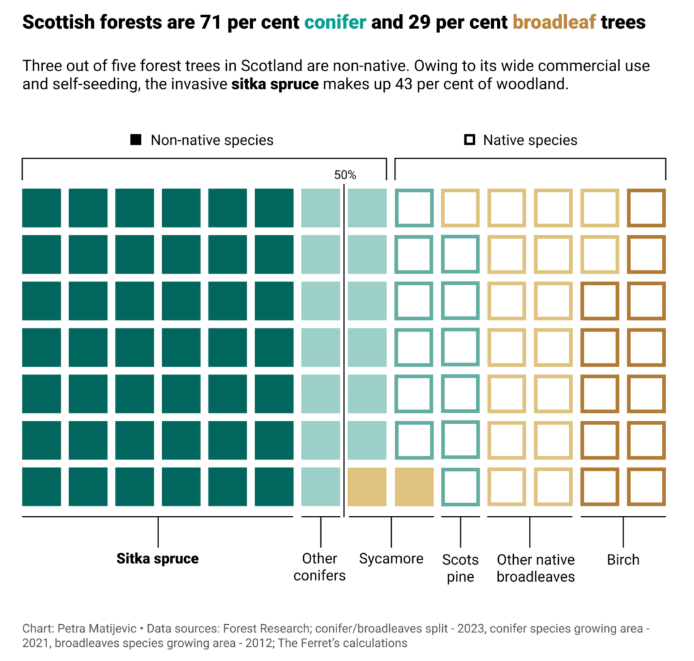

Scotland’s forests overall make up just under 20%. That doesn’t sound so bad, right? Alas, a big chunk of that is made up of Sitka spruce plantations. The Sitka spruce is not native to Scotland - but it sure loves it there. It grows well and tall and makes up a total of over 40% of all of Scottish woodland. The Sitka spruce self-seeds and pops up in ever more places - it also makes it all the harder for other plants (and critters) to make a home.

But then I also read that the fast-growing Sitka spruce shouldn’t be demonized as it helps Scotland on its journey to achieving its net zero targets, that it supports 25’000 jobs and contributes £1bn to the economy. Well, on one hand I’d just say that there’s surely room for both. On the other hand there are plentiful examples of what happens when self-seeding non-native species take over. All too often I see people clinging to what we’ve always done, to what we’re used to. And invariably that means any consideration for nature comes in, at best, as a distant second.

Our families, our communities, our towns, our local and global economies, our entire species - all of it is threatened, if ecosystems continue to be cannibalized. We know that conservation alone (holding on to what is still there) won’t cut it. Restoration is key. And so I’d say that, every non-native plantation tree should, at a minimum, be matched with native trees. Those remnants of native woodlands shouldn’t just be given a fighting chance, they should be getting a steady, long-term boost. I’ve read that the Scottish government wants to grow woodlands from 20% to 32% (by 2032) by creating and restoring native woodlands. Good - as long as that focus really is on native trees, that’ll be a tremendous boost.

What future will we make?

While woodland matters in Scotland are dire, far from everything is bad. Quite the contrary - many good things are happening. Trees for Life writes that the understanding about the importance of Scotland’s native woodlands began to change after World War II.

“People began to make more effort to protect our Caledonian Forest remnants. While there is still much to be done, there is now a huge interest in restoring native woodlands in Scotland with many organisations and individuals on board.”

We cannot and should not go back to the past. The world today is a very different one from the one where those extensive woodlands once flourished. Today our species is here in numbers and that isn’t about to change. Today we also deal with changing climate conditions. In my neck of the woods (Switzerland) we’ve been experiencing climate-change-induced tree changes for years. Ash trees, for example, are suffering and they’ll eventually be gone from here, but still abundant further north. Instead we will say hello to trees that traditionally only lived on the south side of Alps. Things change. Things always change - and that’s neither good nor bad - it just is.

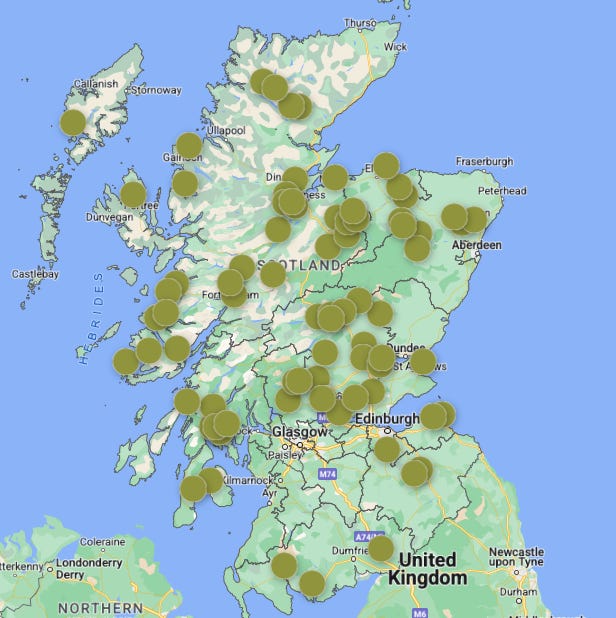

Just to give you a sense of how much is happening to restore native woodlands in Scotland: Here are 84 more places for you to explore - either native woodland growth is their man focus - or a focus area among other nature restoration efforts. In any case, these 84 land partners of Scotland: The Big Picture’s Northwoods Rewilding Network make up a total of over over 23’000 acres of lands with its owners and communities committed to nature restoration. Ever been to New York and wandered the city’s huge lung that is Central Park? Well, you could fit nearly 30 Central Parks into those 23’000 acres.

But that’s far from all, of course: There’s the the unceasing efforts of the Cairngorms National Park with its many national nature reserves. There are the vast Wildland estates (over 200’000 acres owned by philanthropist billionaire Anders Holch Povlsen), focused on nature restoration throughout. There’s the Alliance for Scotland’s Rainforest, a partnership that brings together twenty organizations committed to restoring Scotland’s rainforests. Then there’s Highlands Rewilding with its estates, and the 30-year Affric Highlands project, and Oxygen Conservation’s purchase of the Dorback Estate, and community-driven efforts such as the Tarras Valley Nature Rerserve, and other Povlsen-like “green lairds” like Christopher and Camille Bently and their 5’500 acre Kildrummy Estate … and I’m sure I’ve still only just scratched the surface.

Finally

There are things we cannot control, or at least not in the short-term, but there are countless things we can - and that’s why I am so heartened and hopeful about the work of rewilders across Scotland. What they do is filled with passion, focused on nature AND people, and entirely pragmatic.

The many ongoing projects are in no way, shape or form moonshots, these are no castles in the skies - they are down to earth, they are realistic and they are utterly actionable in our here and now. I’m a huge fan of the campaign to make Scotland the world’s first rewilding nation. It wouldn’t just be a boon for Scotland, it would also be a beacon of can-do hope for the rest of the world. This can happen. Biodiversity-rich nature will be able make a brilliant comeback, if these many sustained efforts to bring back native woodlands not only continue, but continue to grow thanks to funding and laws and the unwavering long-term commitment of so many.

That’s it from me for today.

Cheers,

If you enjoy the Rewilder Weekly …

… please consider supporting my work. Your paid subscription will help generate the funds needed to realize a unique rewilding book I’m working on. And, of course, that paid subscription also ensures that the Rewilder Weekly will always keep going for those who cannot afford to pay. A thousand thanks!